Many people are familiar with the ‘red list’ of threatened animal species. Many Malagasy chameleon species are part of it. On our website, we have included a reference to the endangered status of each species with each species description. This article is intended to shed light on what this is all about.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

What is the ‘red list’?

The ‘Red List’ or ‘Red List of Threatened Species™’ is a list of almost all existing animal species on earth. The species are sorted according to their individual degree of endangerment. The red list therefore indicates whether a species is threatened with extinction, critically endangered or not critical in terms of its global population. However, the red list website not only shows the endangered status, but also provides an overview of the distribution, population size, habitats and ecology of each species.

IUCN headquarters in Gland (Switzerland), photo by Defrenrokorit, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

The Red List is published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN was founded in 1948, has its headquarters in Switzerland and today consists of over 1400 member organisations. The IUCN is one of only two globally active environmental organisations to have observer status at the United Nations.

The data from the Red List is used worldwide when it comes to designating new protected areas, conserving habitats or estimating population sizes. The categorisation into a certain threat status primarily provides the species’ home countries with information on whether and how a chameleon species should be protected. It also influences, for example, whether and to what extent a species is authorised for trade under the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.

How is a chameleon species categorised?

The individual species are discussed and categorised in so-called ‘IUCN Red List Assessments’. To this end, the Species Survival Commission (SSC) invites experts in the relevant field to a meeting – at best every five years, but at the latest every ten. The IUCN SSC Chameleon Specialist Group is responsible for chameleons. It consists of 24 herpetologists, biologists, zoologists and other people who specialise in chameleons. The SSC Chameleon Specialist Group consists exclusively of volunteers, i.e. the group participants are not paid for their work. At its meetings, the Specialist Group discusses the various chameleon species and analyses the current data situation of various species based on the latest publications. It then proposes well-founded changes or new classifications to the IUCN.

When categorising a chameleon species, particular attention is paid to five criteria. The first is the decline in the population size of a species. If a chameleon species is categorised as endangered, declining population sizes must have been observed or a certain population size must have already been determined. However, a species could also be classified as endangered if its range has demonstrably shrunk considerably or if sapphires are mined in many places in its range, for example in Madagascar, or if intensive livestock farming is practised, resulting in massive habitat destruction. A species can also be categorised as endangered if, for example, a rapid decline is to be expected due to introduced species such as domestic cats, interbreeding with other species and thus genetic mixing, certain diseases (the best-known example here is certainly the ‘salamander plague’, even if it has nothing to do with chameleons) or parasites.

Brookesia desperata in the Forêt d’Ambre in northern Madagascar – the species only occurs in a tiny distribution area

A second criterion for categorisation is the distribution of a species. A distinction is made between a possible range (extent of occurrence), i.e. an area in which the chameleon species can theoretically occur, and the actual range (area of occupancy), i.e. the area where the animals actually still live. To be categorised as an endangered species, the distribution area of a chameleon species must be highly fragmented or fall below a certain number of individual populations. In addition, either a steady reduction in the distribution area must have been observed or the number of sexually mature individuals must be steadily declining.

The third criterion for categorisation is population size and decline. A certain low number of mature chameleons in a population together with an estimated decline in population size by a certain percentage over a certain period of time leads to classification as a threatened species. Instead of the total population size, the decline in the number of mature chameleons of a species below a certain number is sufficient for classification.

The fourth criterion for categorisation concerns very small populations. If the number of sexually mature animals in a chameleon population demonstrably falls below a certain level, the species can be categorised as endangered. A special feature applies to vulnerable: if the actual distribution area of a chameleon species is less than 20 km² or has fewer than five individual populations, a species can always be classified in this category.

Finally, to categorise the degree of threat, the probability of extinction of a chameleon species is assessed based on the current data situation. The data from the individual red list assessments are automatically considered outdated after ten years if they have not already been revised during this period.

What threat categories are there?

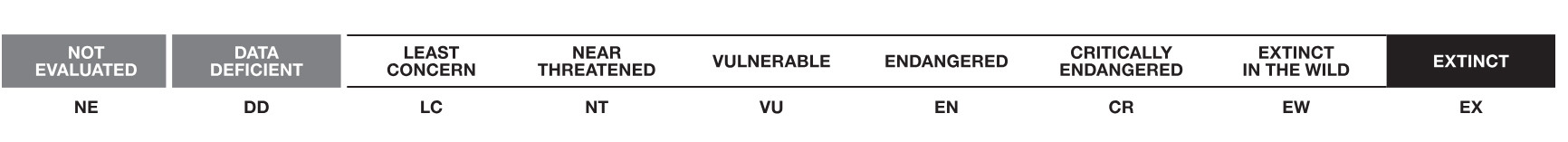

The IUCN categorises red-listed species into one of nine categories, as shown in the following bar. The further to the right a chameleon species is on the list, the more threatened its population is. The categorisations vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered are generally considered ‘threatened’.

Not evaluated

Not evaluated

This categorisation applies to species that have not yet been assessed. These are mostly rediscovered species that were long thought to be lost, such as Furcifer voeltzkowi, or species that have only recently been described, such as Calumma roaloko. These species are not yet included in the red list, so to speak. However, they may already be critically endangered!

Data deficient

Data deficient

There is hardly any knowledge about some chameleon species apart from the fact that they exist and what they look like. They have simply not been researched well enough or not at all. The IUCN does not provide an assessment for these species because not enough data is available. As soon as the data situation changes, the chameleon species can subsequently be categorised as threatened. A Malagasy example of this is the species Brookesia lambertoni. This chameleon has not been found in Madagascar for years and there are almost no publications on its biology, occurrence and appearance apart from the first description.

Least concern

Least concern

There are still very many animals of this chameleon species and/or they are widespread in Madagascar, perhaps not even dependent on specialised habitats. A very good example of this is Madagascar’s most common chameleon, Furcifer oustaleti. This species occurs in extremely many regions of Madagascar and colonises a wide variety of habitats. Rainforest, spiny forest, savannah, secondary vegetation within villages – these chameleons are incredibly adaptable. They are hardly bothered by human colonisation. Juveniles of this species can be found everywhere during the rainy season. Overall, it is not expected that the species will suddenly decline sharply in the next few years. It is therefore categorised as ‘least concern’.

Near threatened

Near threatened

Potentially endangered is the preliminary stage for a threat level. It is assumed that this chameleon species will have to contend with habitat loss or other problems in the coming years. This species could therefore move into the endangered category in the next few years if nothing is done about it.

Vulnerable

Vulnerable

This threat classification is assigned when a species has already been decimated by 30 to 50%. Alternatively, a chameleon species can also be categorised as endangered if this decline can be assumed over a period of 100 years. At the same time, the actual distribution area of the species is already less than 2000 km² or there are only 10 or fewer populations left. There are fewer than 10,000 mature individuals of the species or fewer than 1000 individuals in an individual population and this individual population has declined by 10% in 10 years. The probability that an endangered species will become extinct is 10% or more within the next 100 years.

Endangered

Endangered

A species that is listed under the ‘endangered’ category has already been decimated by 50 to 70%. Alternatively, a chameleon species can also be categorised as critically endangered if this decline can be assumed over a period of 100 years. In addition, the actual distribution area of the species is less than 500 km² or there are only five or even fewer populations left. There are only 2500 sexually mature animals of the species or even fewer. The probability that a critically endangered species will become extinct is 20% or more within the next 20 years.

Critically endangered

Critically endangered

This is the highest threat category. Fortunately, it has only been reached by a few Malagasy chameleon species so far. In a species that is threatened with extinction, the population has already declined by 80 to 90% or this decline is to be expected over a total period of around 100 years. In addition, the species occurs on less than 10 km² or there is only one single population left. There are only 250 or fewer mature individuals of this chameleon species or less than 50 individuals in each population. The risk of this species becoming extinct in the next 10 years is over 50%, which is extremely high.

Extinct in the wild

Extinct in the wild

It is already too late for these animals: there are no more of them left in the wild. However, the species does still exist in zoos or private holdings worldwide. At best, enough animals can be bred from this tiny population to at least preserve the species in human hands.

Extinct

Extinct

A species is considered extinct if there are no animals of it left in the wild or in human hands. According to current scientific knowledge, this species can no longer be saved.

How often is the IUCN data and categorisation updated?

Applications for amendments can be submitted on an ongoing basis. The IUCN updates the red list approximately twice a year. In the case of chameleons, however, the majority of amendments and updates are submitted almost exclusively during the meetings of the SSC Chameleon Specialist Group.

What are the problems with categorising chameleons?

There is not yet much data on many species. And research tends to be conducted on species that are easily accessible, rather than on species that are difficult to find or barely known. We already know that a number of chameleon species in Madagascar exist that probably represent a new species. However, describing a new species today is no longer as easy as it was a hundred years ago. Data and samples have to be collected, permits and funds to finance expeditions have to be painstakingly obtained, the samples have to be analysed and the whole thing has to be evaluated. Many areas are difficult to access and require significantly more effort to get to than elsewhere in the world. But if a chameleon has not been described at all, it is difficult to place it under protection. And species descriptions sometimes take longer than the populations still exist.

Brookesia nofy from the east coast of Madagascar was described in 2024, but is not yet on the red list

Newer species are often not yet categorised. As the Chameleon Specialist Group only meets regularly every few years, it always takes a certain amount of time for the categorisation to be completed. For some species, especially in areas threatened by slash-and-burn, this can simply be a few years too late.

Missing or very outdated data is particularly problematic when categorising chameleon species. If there is only one study on the population of a chameleon species, the population size found there must be assumed. Over the years, however, population sizes can change dramatically and, depending on the location, unexpectedly quickly.

Over time, new information is often added that was not previously known and which greatly changes the assessment of the threat situation of a species. For years, for example, it was assumed that Calumma parsonii parsonii was a pure rainforest inhabitant. Today we know that Parson’s chameleons can also survive well in secondary vegetation such as coffee plantations. A primary forest that no longer exists is therefore less of a problem for this species than, for example, Calumma guillaumeti, which has so far only been found in dense, still completely intact rainforest.

Incomplete data can also lead to misjudgements about the threat situation. Furcifer angeli, a chameleon from western Madagascar, for example, probably still occurs in relatively large numbers on the island. However, the individual populations are very fragmented into small, isolated areas. As a result, the collection of this species, which is actually ‘least concern’, can still lead to the extinction of the respective population in just one place.