The eyes are probably one of the most striking specializations of the chameleon. The chameleon basically has a lens eye like a human being. However, for the purpose of enlarging the field of vision, the two eyes protrude almost completely from the eye sockets and can move independently of each other. The eye itself consists of a double eye chamber.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Eyelids and nictitating membrane

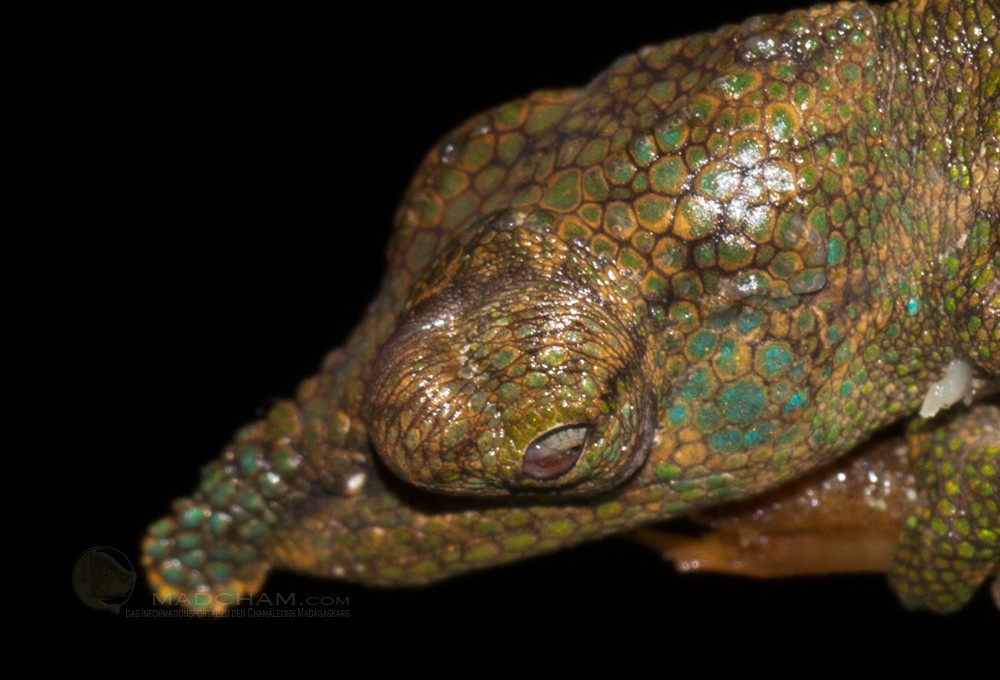

The eyelids of the chameleon are scaly like the whole skin of the animal. The two eyelids are fused together, partly also the eyeball itself is fused with the eyelids. Only one opening remains free in front of the lens. Like the rest of the skin, the eyelids can change color and thus serve as a means of communication. The eyelids are fully enclosed in the skin. Chameleons have, similar to mammals, a “third eyelid”, the so-called nictitating membrane. It lies in the side of the eye facing the nose between the eyelid and the eyeball but is very small, relatively short and contains only tiny cartilage.

Eye muscles

The eye is moved by small muscles that are well hidden under the eyelids and in the eye sockets. The Musculus rectus superior is the widest eye muscle. It runs from the orbit over the eyeball to the front of the eyeball, where it ends directly at the base of the cornea. With this muscle, the cornea is moved back-down. The counterpart, the Musculus rectus inferior consists of two muscle bundles that run under the eyeball to the lower edge of the cornea. It moves the cornea exactly in the opposite direction, downward-middle. Not far from this, the Musculis rectus medialis ends, which causes the cornea to move forwards and midway. There is also the Musculus rectus lateralis, which consists of two parts and is responsible for moving the cornea mid-backward.

The Musculus obliquus superior runs from the orbit to directly below the Musculus rectus superior, i.e. at the top of the eyeball (bulb). It moves the eyeball itself forward and downward. The Musculus obliquus inferior, on the other hand, runs rather horizontally from the orbit to the lower side of the eyeball. With it the eye can be moved upwards.

Scleral cartilage

Similar to birds, chameleons have a small bone ring, the so-called scleral cartilage, in the eye framing the cornea. In many chameleons, these originally cartilaginous structures ossify over time and some of them can even be prepared in the skeleton. The surface of the scleral cartilage is covered with fine muscle fibers belonging to the palpebral depressor muscle.

The lens

Prepared eye of a Parson’s chameleon

The lens is the organ responsible for the refraction of light in the eye. The eye is focused on the curvature of the lens through the corneal muscle. The deformation of the lens is called accommodation. It is believed that the chameleon’s brain uses the extent of eye muscle contraction for accommodation when seeing a prey object to estimate the distance to said object. According to research by Frank Scheffel and Matthias Ott, chameleons can actually vary the lens exactly over 45 diopters. Actions in which the accommodation was not precise enough to catch prey were only 10% in their studies.

When relaxed, the lens has a special property: it does not scatter the light but bundles it. As a result, the visual information is displayed much larger than “normal” on the retina. It has yet to be investigated how this can be achieved – although the lens looks exactly like a biconvex converging lens and would theoretically have a refractive power of about 18 diopters.

The field of view

A chameleon can see 90° vertically and 180° horizontally. The total field of vision is 342°, only above the back directly behind the head there is a blind spot of 18°, in which the chameleon sees nothing.

Keenness of sight

As in humans, visual acuity is caused by the sclera. Because the eyelid covers the entire eye and only a small hole remains free, the chameleon has the effect of a pinhole camera, i.e. additional sharpness. Chameleons can see clearly and sharply up to a distance of one kilometer (!). The focusing speed is about 60 diopters per second (about four times what a human eye is capable of).

Color and contrast vision

The photoreceptors on the retina are responsible for color and contrast vision. They are roughly divided into rods and cones. Chameleons have mainly cones. So they mainly see colors and little contrast, which makes them practically blind in the dark (which is no problem as they are not nocturnal). Oil droplets can accumulate on the cones, which weaken the incidence of light. The chameleon thus has a kind of “built-in sunglasses” to protect the eye. Lindsay Harkness estimated the number of cones in a chameleon eye at about 756,000 pieces per mm² of the retina – that is a lot compared to other reptiles.

Eyes and behavior

In a hunting chameleon, the eyes constantly and independently scan the surroundings. Only when the food animal is focused on both eyes, the chameleon shoots at it. The correct estimation of the distance to a feeding animal is essential for a successful tongue shot.

When the chameleon sleeps, it closes its eyelids. It can lower its eyeballs in addition to protection by means of the palpebral depressor muscle to protect the sensitive pupil. This muscle runs from the eyelid gap around the lower part of the eyeball to the lower part of the orbit. The function of the muscle is also used to clean the eye. Especially when you observe this behavior for the first time, it can seem very strange: Once something has landed in the eye, the chameleon can press its eyeball against the eyelids far forward out of the orbit. The nictitating membrane is pushed upwards and a kind of wiping movement is performed on the front part of the eyeball. Usually, the eye is additionally rubbed against a branch to remove the foreign body. The advancing of the eyes can also be observed before molting. As long as it does not reappear several times a day or over a longer period of time, this behavior is not a cause for concern.

Chameleons can also pull their eyes inwards, for example during stress. Under normal conditions, however, “sunken eyes” are often a symptom of a disease.