Anatomy means as much as the study of the structure of the body. This site is dedicated to the anatomy of Madagascan chameleons, and it is certainly not complete. We expand the article piece by piece so that it becomes as complete as possible at some point. Since organs such as lungs and liver are also discussed here, we would like to point out that photos of sections or internal organs of chameleons can be seen in this article. The table of contents on the right can be folded out and back in to make the article easier to read.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Skeleton

The skeleton of a chameleon is primarily its bones and cartilage. The bones of chameleons are not hollow but filled with bone marrow. Every one of the skeleton has a scientific name, and almost every point or extension of the bones can be addressed again with its own terms. For simplicity’s sake, not all bone points and parts are mentioned in our explanations.

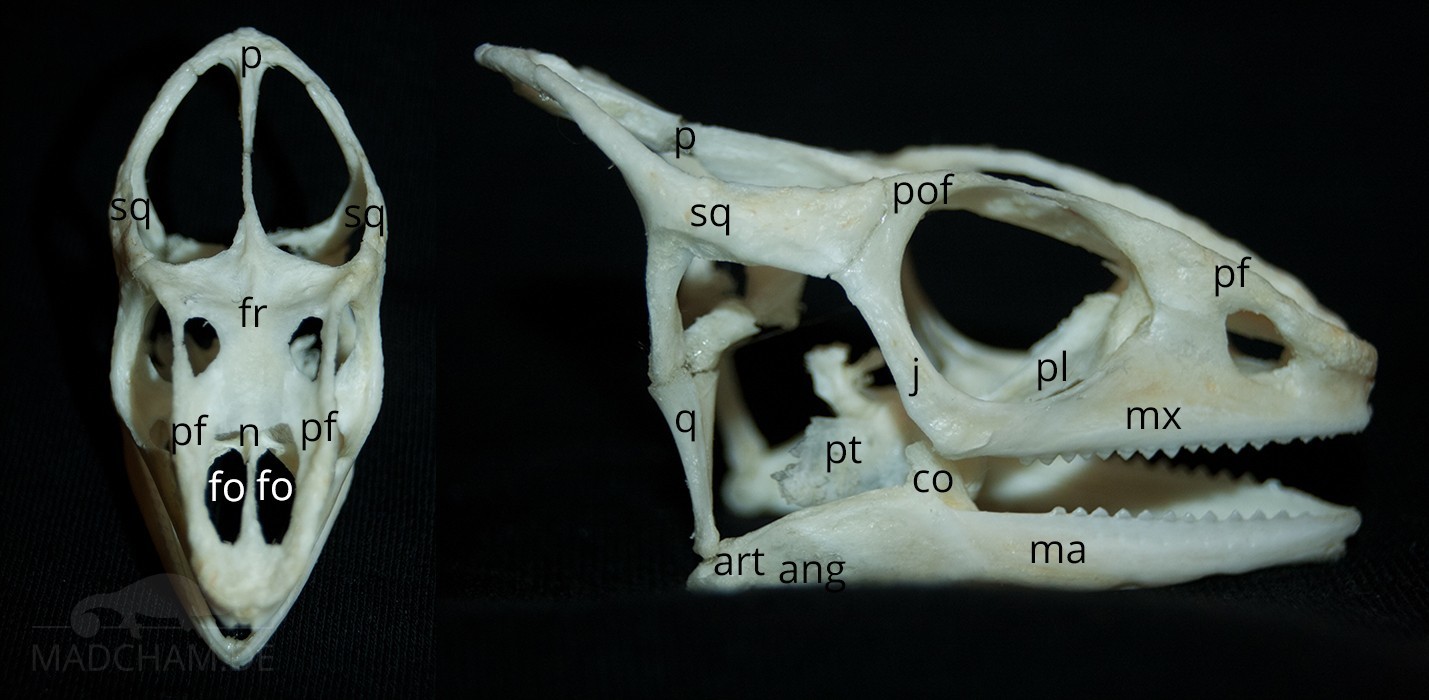

Head

The head of a chameleon – explained here on a panther chameleon – consists, as in humans, of the upper jaw with the skull and the lower jaw. The lower jaw consists of Os mandibulare (lower jaw bone, ma), which consists of the anterior region with the teeth and the joint area (articular, art) at the very back and between the angular (ang) os. A small projection that projects upwards is called Os coronoideus (raven process, co). Chameleons are acrodont, i.e. the teeth sit vertically on the jawbone and are part of it. There is no mammalian separation between the tooth cavity and the tooth inside. Chameleon teeth are therefore of course not changed and cannot fall out, but remain for a lifetime.

The skull is formed by the wide frontal os (fr), the two preceding prefrontals (pf), the small nasal os (nasal bone, n) between them, and the upper jaw (maxillaries, mx). The orbit is formed by the postorbitofrontal (pof) and zygomatic bone (jugular, j). The casquefollows with the Os parietale to the Os frontale. Depending on the species of chameleon, these skull bones can be very different. On the side, the casque is limited by the two Os squamale (sq). The underlying Os quadratum (q) forms the joint to the lower jaw. Especially in the upper jaw of chameleons, as in other reptiles, the so-called choanae are inside the palate. The choanae are holes in the hard palate, so to speak, in humans, it would be called a cleft palate. In chameleons, however, this connection between the mouth and nose is completely normal.

The hyoid is attached to the head with connective tissue. Since it is essential for the tongue shot typical of chameleons, the hyoid bone is discussed in the corresponding article.

Spine and ribs

The spine (1) of chameleons is particularly long and consists of cervical, dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae. In most species, the spine is not subdivided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae; instead, both are simply considered to be dorsal vertebrae. The number of vertebrae varies depending on the species, but the number of cervical vertebrae is always five. The spinous processes of the vertebrae differ between all species. In leaf chameleons of the genus Brookesia they are hardly developed, so their vertebrae rather show a bony bridge at the top. Brookesia perarmata is known to have only two morphologically distinct vertebral regions in its trunk spine. The species also has the smallest number of trunk vertebrae.

What is special about chameleons is that the ribs (2) do not only reach over the thoracic vertebrae, but also to the sacrum. This protects the entire chest and abdomen with all its organs. In contrast to mammals, chameleons have only a few free ribs, but almost all ribs are firmly connected to the sternum (3) or the opposite cartilage process of the opposite rib via connective tissue and cartilages. Palpation of the belly is therefore often of little use in chameleons since the belly cannot be palpated softly as in mammals. Only the very last rib extensions directly on the sacrum are very small and only attached in connective tissue, and the first ribs are usually anchored in the shoulder belt in connective tissue.

Skeleton of a female Parson’s chameleon

The tail is usually as long as the body itself and is used for holding on and climbing. It cannot be discarded or regenerated in chameleons. Sleeping or threatening chameleons roll the tail completely in. The tail can only be rolled in one direction, downwards.

Extremities

The extremities of a chameleon are basically constructed exactly like those of humans, but in a completely different shape: there are also the shoulder blade (4), upper arm (5), ulna and spoke (6) as well as hip (9), thigh (10) and tibia and fibula (11). Fingers and toes form quasi small gripping tongs, which form an optimal adaptation to the climbing way of life. At the front limbs two fingers are directed outwards and three inwards (7), at the hind limbs it is exactly the other way around (8): Two toes inwards, three-point outwards. The phenomenon of “fingers and toes have grown together” is called syndactyly. In fact, the bones themselves are not fused together.

The hip (9) is only sinewy connected to the sacrum, which can sometimes lead to “protruding” hips if this tissue is weakened or absent. It is similar to the shoulder blades, these also only sit on the ribs sinewy, but are additionally connected to the sternum (3). From time to time, “protruding” bones can also be observed on the shoulders, but these usually do not disturb the affected chameleon.

Skin

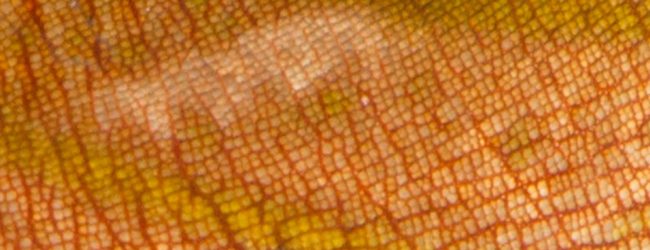

As with all animals, the skin of the chameleons consists of three layers: Upper, leather, and subcutis. The epidermis with its keratinized outermost cell layer forms the typical scales. It is an external protective barrier against injury and moisture loss and simultaneously serves to change the colour of communication. If the chameleon grows, it must from time to time remove the top layer of skin, as this does not grow with it – the animal skins itself. Chameleons cannot store fat in the skin, as mammals do.

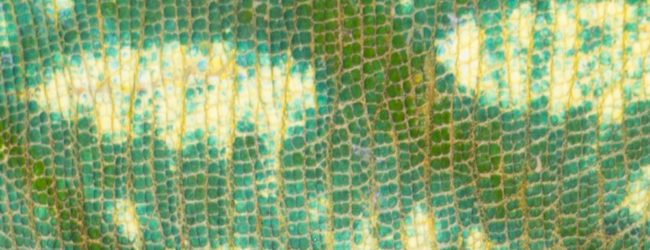

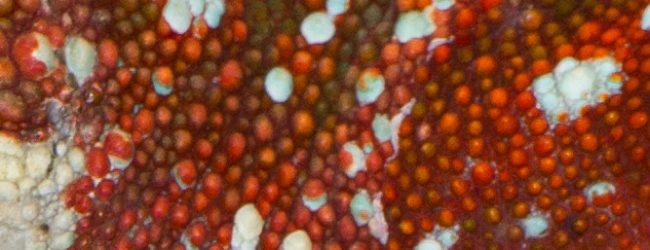

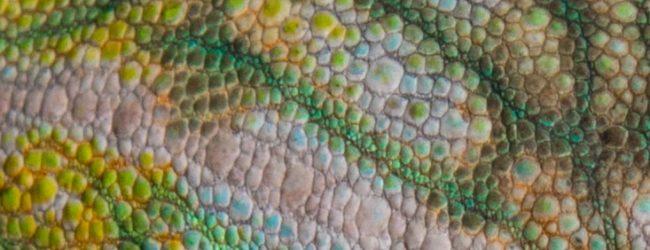

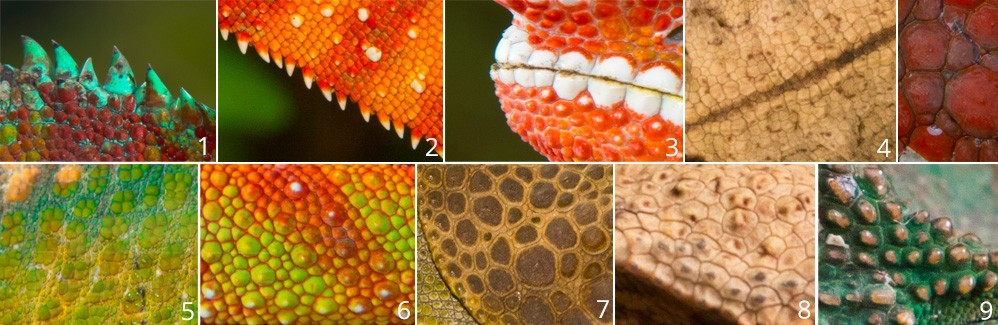

The scales of chameleons vary from species to species and sometimes even from body part to body part. Through these scales, the extremely different skin structures of the different species develop. The scaly structure is roughly divided into homogeneous, i.e. uniform, similarly sized scales next to each other as seen above in Calumma glawi, and heterogeneous scalation, whereby the scales are of different sizes, as seen above in Furcifer rhinoceratus.

The scales are divided into different types, which differ slightly depending on the author. The simplest type of shed is the conical scale (1 and 2) – the name says it all. These scales can be found mainly on the dorsal and ventral crest, as here in the picture with panther chameleons. The so-called labial scales (3) are found along the lips and are usually white or at least lighter in color than their surroundings. Here, too, the panther chameleon is a good example. Keeled scales (4), on the other hand, can be found mainly in various Brookesia species. Granular scales (5) are often found as small accumulations between larger scales, as shown in figure 5. Among the tubercle scales (9), which often occur on the crests of the skull, many authors also include the lenticular scales (6) scales, also raised in the middle, and the plate-like scales (7), as here on the occipital lobes of Calumma brevicorne. Star-shaped and polygonal scales (8) are also descendants, here on the skin of Brookesia decaryi.

Crests

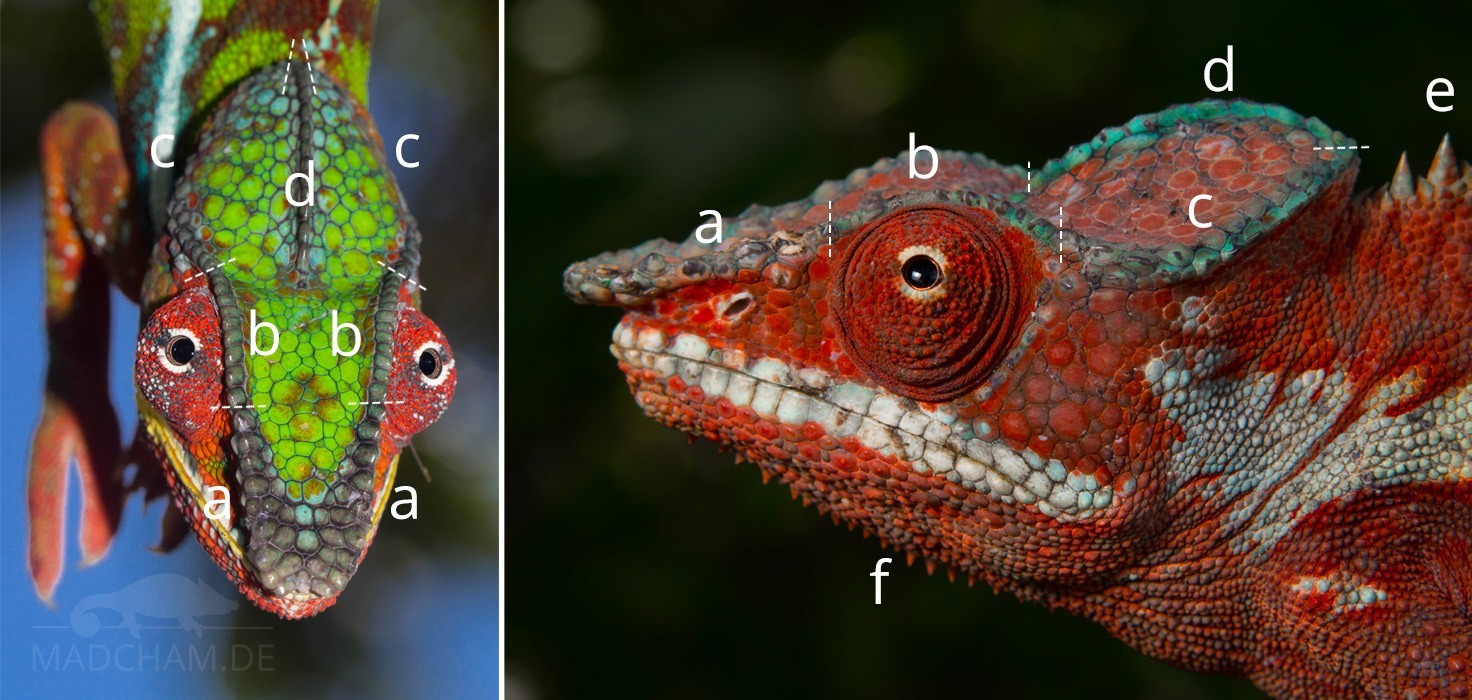

To describe and distinguish between chameleons, so-called crests are often used, which the chameleon can wear on different parts of the body. There are several of them on the skull: The lateral crest (a-c) consists of three parts. The rostral part (rostral crest, a) runs from the tip of the nose to just before the eye, the orbital part (orbital crest, b) runs – as the name suggests – over the eye, and the third part (proper lateral crest, c) runs from just behind the eye to the tip of the helmet. Of many chameleon keepers, only the bone crest from the eye to the tip of the helmet is called the lateral crest. The parietal crest (d) also runs in the middle of the helmet. In some chameleon species, there is an additional temporal crest at the head, which runs between the parietal crest and the eye.

Most chameleon species also have crests that are not formed by underlying bones, but merely consist of conical scales. This includes the dorsal crest (e), which varies greatly from species to species. Some species such as panther chameleons carry a continuous row of cone-shaped scales on their backs, others like the females of Furcifer antimena only sporadically or only in the anterior area. The counterpart to the dorsal crest is the ventral crest (not pictures), which runs naturally along the abdomen. However, the area from the chin to the chest is still divided into the so-called gular crest (f).

Occipital lobes

Some Madagascan chameleons have lobed appendages behind their heads that are often confused with ears. They have nothing to do with ears, they are so-called occipital lobes. These are skin appendages, in larger species partly with a cartilaginous base. If the occipital lobes are quite large, they can be straightened up with the help of the Musculus depressor mandibulae when threatened and make the chameleon appear larger. The occipital lobes are also often used to differentiate between species.

Rostral appendages

Many chameleons have nasal appendages. A distinction is made between real horns, which consist of a single, enlarged, keratinized scale on a bony projection, and false horns, which also have a bony basis but are covered by completely normal skin scales.

Real horns can be found in many African Trioceros species, for example.

There are only chameleons with false horns in Madagascar. Often these nasal processes are bony processes resulting from the two rostral bone combs of the head, which grow together to a single process in front. An example of such a nasal process is Furcifer rhinoceratus. In Madagascar, however, there are also bilateral extensions of the rostral bone ridges such as Furcifer balteatus, Furcifer bifidus, Furcifer minor, or Calumma parsonii. In many leaf chameleons, the false horns have become bony appendages along the lateral bone crest or appendages between the mouth and nose in the course of evolution.

Another variant of chameleons is a nasal processes without a bony basis, the dermal horns (“skin horns”). They consist only of soft skin and are correspondingly flexible. These rostral appendages can be found for example in Calumma gallus or Calumma nasutum.

Senses

Sense of smell

The odor-sensitive epithelium is present in the nose of lizards and the Jacobson’s organ (also called Vomeronasal organ) on the palate. It is believed to play a role in tongue testing behavior. However, it has been proven that the Jacobson’s organ in chameleons, unlike snakes, is rather poorly developed. The sense of smell therefore seems to play a minor role.

Sense of taste

In chameleons, taste buds are mainly located at the tip of the tongue and the tongue pad. Overall, fewer of them are present than in other reptiles.

Hearing and balance

Just like mammals, chameleons have a sense of balance and rotation as well as a sense of hearing. An outer ear with an eardrum cannot be found, and the remaining auditory ossicle (Columella) is so severely reduced in many species that it can hardly be called functional. Nevertheless, chameleons can probably hear very loud and low-frequency noises around 200 Hz. They also react strongly to vibrations.

Special glands of the head

Salt glands

The nose of the chameleons has salt glands through which excess minerals can be excreted in crystalline form. Above all, these are potassium and sodium. The animal can save water by the precipitation of the salts. Contrary to rumors to the contrary, the appearance of salts on the nose of chameleons has nothing to do with the fact that the animal in question is supplemented too much. Calcium is not one of the excreted minerals!

Temporal glands

The temporal glands that are not present in all chameleons are located in the corners of the mouth. They always secrete a little, but you can hardly see with the naked eye. However, the yellowish discoloration of the corners of the mouth in many chameleons testifies to the activity of the glands. According to studies by Ogilvie, the secretion mainly contains horny skin cells whose function has not yet been fully clarified. It is discussed whether the secretion is used to mark branches, or simply as a result of the increasingly clashing skin layers in the corner of the mouth.

Respiratory tract

Windpipe and gular pouch

The trachea in chameleons has incompletely closed cartilage braces. It divides into the two main bronchi at heart level. Several chameleon species have an additional, smaller so-called gular pouch. The anatomy of these additional air sacs can vary greatly between species as well as within species. So, some animals have only one easily “bulged” trachea at this place, others a single air sac, again others equal three or four smaller air sacs. It is assumed that this diversity of these gular pouches can be used for intra-species communication via vibrations. The following overview provides information about the Malagasy species and their forms of the gular pouch.

| Chameleon species |

Gular pouch? | If yes, how does it look like? |

| Brookesia decaryi | no | |

| Brookesia perarmata | no | |

| Brookesia stumpffi | no | |

| Brookesia superciliaris | no | |

| Brookesia thieli | no | |

| Calumma brevicorne | no | |

| Calumma crypticum | no | |

| Calumma gastrotaenia | no | |

| Calumma malthe | no | |

| Calumma nasutum | no | |

| Calumma oshaughnessyi | no | |

| Calumma parsonii cristifer | no | |

| Calumma parsonii parsonii | no | |

| Furcifer balteatus | yes | one single gular pouch |

| Furcifer campani | no | – |

| Furcifer lateralis | intermediate | a small bulge at the trachea |

| Furcifer oustaleti | yes | one to three gular pouches |

| Furcifer pardalis | intermediate | a small bulge at the trachea |

| Furcifer petteri | no | – |

| Furcifer verrucosus | yes | two to four gular pouches |

| Furcifer willsii | no |

Lungs and air sacs

The respiratory system of the chameleon is completely different from that of mammals. Although the lung is also paired, it is more reminiscent of a sack with numerous finger-shaped bulges than of the solid tissue of the human lung consisting of countless alveoli. The lungs of chameleons are divided by thin septa into different areas (“air sacs”), which reach far back into the body with fine branches. The subdivisions vary from species to species.

Both inhalation and exhalation are controlled by active movements of the intercostal muscles (compared with mammals, only inhalation and a very short part of exhalation by muscles are forced). With a single breath, however, a chameleon can achieve twice the oxygen supply of its blood, since the gas exchange in these animals takes place both during inhalation and exhalation (this mainly happens in the front area of the lung, the protruding bulges in the abdomen do not serve the gas exchange).

Due to the sack-like shape, the filigree, extremely thin membranes, and relatively poor blood circulation, the chameleon lung is unfortunately very susceptible to infections, which requires special attention, especially in terrariums. With adequate lighting, water supply, and ventilation, temperatures and humidity must optimally meet the chameleon’s requirements. The animals cannot cough (because there is no diaphragm), which prevents them from transporting liquid in the air sacs upwards through the windpipe. At the latest slime in the mouth, audible breathing noises and constantly opened mouth despite low temperatures should be for the owner alarm signals to visit the next chameleon-conscious veterinarian. Lung diseases are not harmless and can be fatal in chameleons.

In addition to breathing, the air sacs also serve to change its shape: for example, when a chameleon threatens, it can literally “inflate” and change its body shape considerably. This inflation function is also used when the animals drop: This cushions the fall and usually nothing happens to the chameleon.

Heart

The heart of the chameleon has two separate atria, but only one chamber. Muscle slats can almost completely separate this heart chamber into two independent areas. This is usually the case with thermostable animals. As soon as the muscle slats let blood pass, body, and lung circulation are connected. This allows the animal to move blood between the two cycles as needed, which means it can adapt very well to changing environmental conditions.

In principle, low-oxygen, “used” blood flows from the body via the veins into the right atrium and is then pumped out of the chamber into the lungs, where oxygen is absorbed. The oxygen-rich blood from the lungs then flows into the left atrium, from the ventricle it is then transferred into the body’s circulation. Because chameleons have only one ventricle instead of two like mammals, they can regulate acid-base balance, gas exchange, and blood pressure much more efficiently at different body temperatures.

Lymphatic system

The body’s lymphatic system transports fluid (lymph) from tissues and organs to the veins so that they can return to the body’s circulation. The lymphatic system is developed in chameleons, but there are no lymph nodes as in humans. At least lymph follicles are present in the gastrointestinal tract.

Spleen

The spleen of the chameleon is usually located in the upper intestinal mesentery. It is small and round in relation to body size.

Thymus

The thymus consists of two small lobules, each located laterally of the throat under the internal carotid artery and in the middle of the jugular veins. This is no longer found in adult animals.

Liver and gall bladder

As with all lizards, the chameleon’s liver consists of only two elongated lobes reaching into the back half of the body. The left lobe of the liver is slightly larger than the right. There’s a gall bladder in the direction of the stomach in the left lobe of the liver. Depending on the type of chameleon, the shape of the liver is slightly different.

Gastrointestinal tract

The stomach and intestines are similar to mammals, but the digestion of chameleons depends very much on body temperature, water balance, feed size, and species. At optimum temperature, digestion can take place many times faster than at cool temperatures. The entire passage of a food animal from the exit of the stomach to the remains in the cloaca takes on average about three days, with smaller animals only one day is possible. This is significantly longer than the intestinal passage in mammals (several hours). The entire intestine, in some species only a part of it, is black pigmented in chameleons – this is also rather unusual in the animal kingdom.

Abdominal fat bodies

Chameleons show only minimal obesity from the outside, if at all. Instead, the fat storage of the animals lies in the abdomen in the form of two long, broad fat bodies under the ribs. These abdominal fat bodies can take on considerable proportions in overfed animals and reach under the lungs. Chameleons do not store their fat “on the inner organs”, but only in this specially created fat body.

Urogenital tract

Renal and adrenal glands

Chameleons have a renal portal vein system. This means that blood from the body can be sent directly to the kidney through the veins, not only to the liver as in mammals. The kidneys lie directly under the sacrum and are elongated, smooth structures. The adrenal glands are located directly in front of it as small, yellowish glands (however, it is discussed whether they are present in all chameleon species). The paired kidneys have only a few nephrons (kidney corpuscles). The last tubule segment is a so-called sexual segment, but its exact function is unclear. Chameleons do not have a Henle’s loop, with whose help mammals can concentrate their urine – thereby water is withdrawn. Instead, they excrete uric acid crystals, i.e. urate, directly. Chameleons also lack a renal pelvis or paper pills into which the collecting tubes of the kidney flow in mammals, but the collecting tubes flow directly into the ureter.

Bladder and cloaca

The cloaca itself functions as a joint outlet for urine and feces, i.e. the ureter, the urethra, and the rectum flow into the cloaca. It is divided into three sections: Coprodeum, urodeum, and proctodeum. Many chameleons have a small bladder, but not all of them. It lies in close contact with the abdominal fat bodies and has a urethra that ends in the cloaca. In male animals, the urethra and spermatic duct usually end on the so-called Papilla urogenitalis in the urodaeum. In female animals, however, the urethra and fallopian tubes run separately to the cloaca.

Sexual organs

Male chameleons not only have one penis but two hemipenes. These are in pockets behind the cloaca. On top of each hemipenis, there is a narrow channel that transports the sperm into the cloaca of the female during mating. The hemipenes with their specific appearance (including the various papillae on them) are also used for species differentiation.

Female chameleons are either oviparous (lay soft-shelled eggs) or ovoviviparous (bear live young surrounded by a thin egg skin). The animals have ovaries and the so-called laying intestine, which flows into the cesspool. When laying eggs, the area of the cloaca can be turned over so that the eggs do not come into complete contact with excrement or urate.

Sexual maturity in lizards is determined by height or weight, not by age.

Sexual characteristics

Most chameleon species show a strong sexual dimorphism. The males are larger and more colorfully colored in many species, and in some species, they have typical nasal processes or altered ridges. In the panther chameleon, for example, the male is larger and more colorful, while the female is smaller and remains pink. In Furcifer rhinoceratus, on the other hand, the males do not impress by size, but by a conspicuous nasal process. Here it is the females that wear striking colors.

The tail of a male chameleon is clearly thickened by the two hemipenes pockets in most species. However, one should not confuse this thickening with the cloaca, which is located further forward at the tail base.

Endocrine organs

Endocrine organs include the epi- and pituitary gland, thyroid gland, adrenal glands (already mentioned in the chapter Urogenital tract), Langerhans’ islets of the pancreas, and the gonads (also explained in the chapter Urogenital tract), possibly also the parietal gland. A special feature of lizards is the ultimobranchial gland, which produces calcitonin (a hormone) separately from the thyroid gland.