Shedding

Chameleons grow for a lifetime. Since their skin cannot grow with them, they have to shed it from time to time. This process is called molting or shedding. The anatomical term is ecdysis, derived from the ancient Greek ἐκδύω (ekduo), which means “to strip”. This is a nice way to describe the process: The chameleon removes its old skin during the shedding process like old clothes and keeps the new “clothes” on.

Shedding trigger

Shedding residues on the head of a Calumma linotum in Amber Mountain rainforest

In lizards, including chameleons, it is assumed that the thyroid gland secretes more hormones such as thyroxine before shedding. These are responsible for the shedding process of the epidermis. With snakes, by the way, it is exactly the other way around: an increased release of thyroxine from the thyroid gland slows down the molting intervals instead of stimulating new molting. The thyroid gland is controlled by the pituitary gland, among others.

The process of shedding

The molting begins even before we can see it with the naked eye on the chameleon. You can divide the whole process into different stages. The first stage is the normal state of the skin, i.e. the state during which the chameleon is not shedding its skin. The other five stages deal with the shedding process.

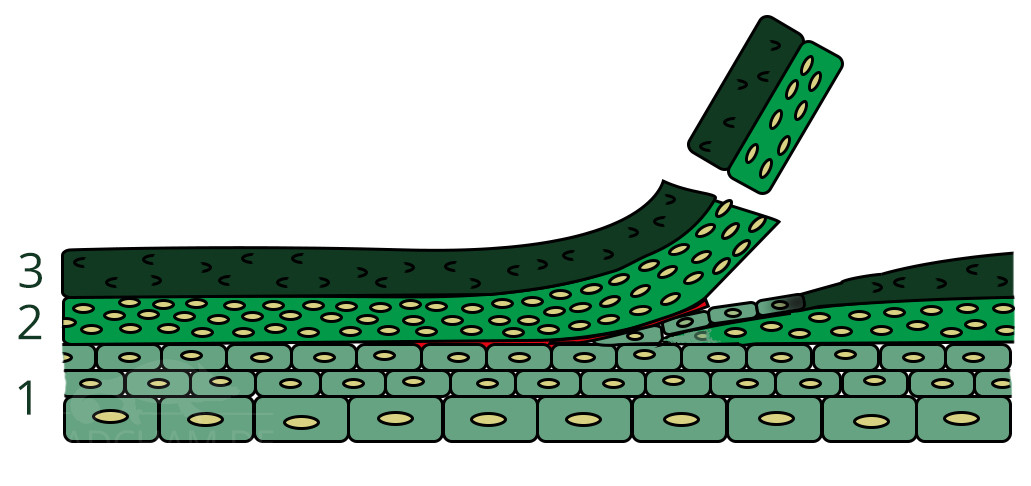

Only the epidermis, i.e. the outermost skin layer of the chameleon, is involved in molting. In the resting state, it consists – from bottom to top – of the germinal layer (Stratum germinativum), the granular layer (Stratum ganulosum), and the horny layer (Stratum corneum). The granular layer has a film rich in lipids, which plays a major role in making the skin “waterproof”. The outer horny layer is the strongly keratinized layer that forms the scales of the chameleon. There are α and β keratin, which form the horny layer in superimposed layers. The α keratin is soft and forms the inner part of the scales and the soft area between the individual scales. It ensures that a chameleon can inflate its gular sac and change its body shape. The β keratin on the other hand provides the hard, outer part of a scale.

Schematic sequence of a shedding with Stratum germinativum (1), Stratum granulosum (2), and Stratum corneum (3). The intermediate layer between old and new skin is shown in red.

The germinative layer of the epidermis builds up an additional granular layer and horny layer for shedding. It virtually builds up the same skin layers again under the old layers. Between the old and new skin layers an intermediate layer develops, the Stratum intermedium. White blood cells (heterophilic granulocytes) and lymphatic fluid migrate into this intermediate layer. This process can now be observed in the chameleon: The skin suddenly appears milky. The proteolytic enzymes of the lymph ensure that the old skin layer is gradually detached. This is the final stage of shedding. At this stage, you can see on the chameleon that the “old skin” bursts open and detaches itself. At first, there are still shreds hanging all over the chameleon, but little by little the remains of the skin are lost. The already stripped off “old” skin is called exuvia. This term is borrowed from the Latin exuviae. It means as much as “that which has been stripped off”. The hemipenes also shed their skin every time, and thus, after shedding, the remains of it are sometimes found in the vicinity of male chameleons in the form of small, yellowish, wrinkled strands.

Shedding residues from the hemipenes pockets

The molting processes in reptiles have so far been studied mainly in snakes and some geckos. Since they are very similar, it is assumed that reptiles that have not been studied also shed their skin in the same way or only with very small differences in the process. Unfortunately, there are no studies on the molting process of chameleons.

Influencing factors

The shedding process is largely controlled by the health of the chameleon. Sick chameleons do not molt well and often shedding residues remain. Furthermore, molting only works if the ambient temperature is right. As ectothermic reptiles, chameleons depend on heat to ensure that all processes of the body function – shedding is no exception. In Madagascar, molting works best during the rainy season, when there is the best food supply and most growth takes place. In addition, during the rainy season, there is increased humidity, which makes shedding easier.

During the shedding process, the new skin is still very soft, which makes it more susceptible to parasites and infections. This unfortunately directly destroys the actual practical effect that chameleons can get rid of annoying parasites by shedding in the wilderness of Madagascar.

Shedding of a Furcifer verrucosus in Ifaty

Changes in behavior

Many chameleons change their behavior during a molt. First of all, some animals stop eating shortly before and during molting. Others become more aggressive than usual. During the shedding process itself, most chameleons try to scrape the remains of the molt off branches or rub body parts like the eyes on plants to get disturbing skin shreds out of sight. Although it is rarely observed in chameleons, there are some individuals that eat the exuviae.

Duration of shedding

Chameleons grow for a lifetime, which means that they will continue to shed their skin for the rest of their lives. Young animals quickly shed their skin all over their body within a few hours. The older the chameleon becomes, the slower it sheds. A moult can then take one or two weeks and only occur every few months. In adult animals it is also normal if only parts of the body are shed. Sometimes the head is on, sometimes the tail, then a leg.